COVID-19 JobKeeper Payment

Ian Campbell • 5 April 2020

$130 billion JobKeeper payment to keep Australians in a job

On 30.3.2020, it was announced The Federal Government will provide a historic wage subsidy to around 6 million workers who will receive a flat payment of $1,500 per fortnight through their employer, before tax.

The $130 billion JobKeeper payment is aimed to keep Australians in jobs as employers tackle the significant economic impact from the coronavirus.

The payment will be open to eligible businesses that receive a significant financial hit caused by the coronavirus.

The payment will provide the equivalent of around 70 per cent of the national median wage.

For workers in the accommodation, hospitality and retail sectors it will equate to a full median replacement wage.

The payment will ensure eligible employers and employees stay connected while some businesses move into hibernation.

This JobKeeper payment will bring the Government’s total economic support for the economy to $320 billion or 16.4 per cent of GDP.

JobKeeper Payment

The JobKeeper Payment is a subsidy to businesses, which will keep more Australians in jobs through the course of the coronavirus outbreak.

The payment will be paid to employers, for up to six months, for each eligible employee that was on their books on 1 March 2020 and is retained or continues to be engaged by that employer.

Where a business has stood down employees since 1 March, the payment will help them maintain connection with their employees.

Employers will receive a payment of $1,500 per fortnight per eligible employee. Every eligible employee must receive at least $1,500 per fortnight from this business, before tax.

The program commenced on 30 March 2020, with the first payments to be received by eligible businesses in the first week of May as monthly arrears from the Australian Taxation Office. Eligible businesses can begin distributing the JobKeeper payment immediately and will be reimbursed from the first week of May.

The Government will provide updates on further business cashflow support in coming days.

Eligible employers will be those with annual turnover of less than $1 billion who self-assess that have a reduction in revenue of 30 per cent or more, since 1 March 2020 over a minimum one-month period.

Employers with an annual turnover of $1 billion or more would be required to demonstrate a reduction in revenue of 50 per cent or more to be eligible. Businesses subject to the Major Bank Levy will not be eligible.

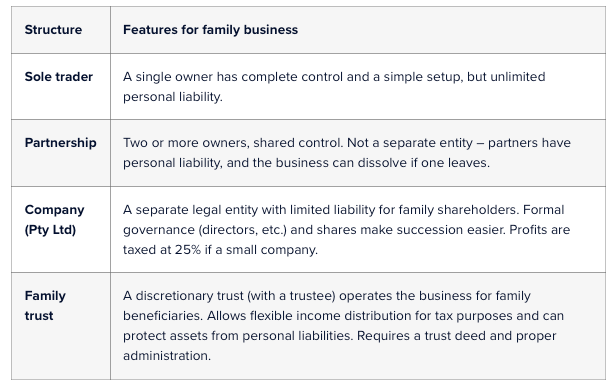

Eligible employers include businesses structured through companies, partnerships, trusts and sole traders. Not for profit entities, including charities, will also be eligible.

Full time and part time employees, including stood down employees, would be eligible to receive the JobKeeper Payment. Where a casual employee has been with their employer for at least the previous 12 months they will also be eligible for the Payment. An employee will only be eligible to receive this payment from one employer.

Eligible employees include Australian residents, New Zealand citizens in Australia who hold a subclass 444 special category visa, and migrants who are eligible for JobSeeker Payment or Youth Allowance (Other).

Self-employed individuals are also eligible to receive the JobKeeper Payment.

Eligible businesses can apply for the payment online and are able to register their interest via ato.gov.au

Income support partner pay income test

Over the next six months the Government is temporarily expanding access to income support payments and establishing a Coronavirus Supplement of $550 per fortnight.

JobSeeker Payment is subject to a partner income test, and from 30.3.2020 the Government is temporarily relaxing the partner income test to ensure that an eligible person can receive the JobSeeker Payment, and associated Coronavirus Supplement, providing their partner earns less than $3,068 per fortnight, around $79,762 per annum.

The personal income test for individuals on JobSeeker Payment will still apply.

Downloadable Resource

A real-world case study on trust distributions Mark and Lisa had what most people would describe as a “pretty standard” setup. They ran a successful family business through a discretionary trust. The trust had been in place for years, established when the business was small and cash was tight. Over time, the business grew, profits improved, and the trust started distributing decent amounts of income each year. The tax returns were lodged. Nobody had ever had a problem with the ATO. So naturally, they assumed everything was fine. This is where the story starts to get interesting. Year one: the harmless decision In a good year, the business made about $280,000. It was suggested that some income be distributed to Mark and Lisa’s two adult children, Josh and Emily. Both were over 18, both were studying, and neither earned much income. On paper, it made sense. Josh received $40,000. Emily received $40,000. The rest was split between Mark, Lisa, and a company beneficiary. The tax bill went down. Everyone was happy. But here’s the first quiet detail that mattered later. Josh and Emily never actually received the money. No bank transfer. No separate accounts. No conversations about what they wanted to do with it. The trust kept the funds in its main business account and used them to pay suppliers and reduce debt. At the time, nobody thought twice. “It’s still family money.” “They can access it if they need it.” “We’ll square it up later.” These are very common thoughts. And this is exactly where risk quietly begins. Year two: things get a little more complicated The next year was even better. They used a bucket company to cap tax at the company rate. Again, a common and legitimate strategy when used properly. So the trust distributed $200,000 to the company. No cash moved. It was recorded as an unpaid present entitlement. The idea was that the company would get paid later, when cash flow allowed. Meanwhile, the trust needed funds to buy new equipment and cover a short-term cash squeeze. The trust borrowed money from the company. There was a loan agreement. Interest was charged. Everything looked tidy on paper. From the outside, it all seemed sensible. But economically, nothing really changed. The trust made money. The trust kept using the money. The same people controlled everything. The bucket company never actually used the funds for its own business or investments. This detail becomes important later. Year three: circular money without anyone realising By year three, things had become routine. Distributions were made to the kids again. The bucket company received another entitlement. Loans were adjusted at year-end through journal entries. What is really happening is a circular flow. Money was being allocated to beneficiaries, then effectively coming back to the trust, either because it was never paid out or because it was loaned back almost immediately. No one was trying to hide anything. No one thought they were doing the wrong thing. They were just following what they’d always done. This is how section 100A issues usually arise. Slowly, quietly, and without any single dramatic mistake.

Rental deductions maximisation strategies