Practice Update November 2025

A Practical Guide to Running Your Family Business in Australia

Family businesses are the backbone of Australia’s economy, accounting for roughly 70% of all businesses. From farms to cafes and construction firms, many local enterprises are family-owned. Running a family business can be incredibly rewarding – you’re building a legacy and working with loved ones. However, it also brings unique challenges, as family emotions and business decisions often mix when the dining table doubles as the boardroom. This article outlines key legal, accounting, tax, and strategic tips to help small- to medium-sized family businesses succeed.

Choosing the proper business structure

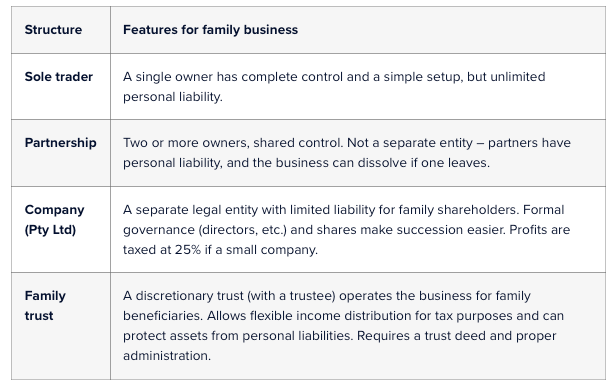

One of the first steps is deciding on a structure. Common options include sole trader, partnership, company, and family trust. Each has different implications for liability, tax and control:

It’s wise to consult an accountant or lawyer when choosing a structure, as the decision affects your taxes, legal obligations and how family members can be involved. For example, a discretionary trust lets you split income tax-effectively among relatives, while a company structure makes it easier to transfer ownership to the next generation via shares.

Example: A husband-and-wife team running a café might start as a simple partnership, but as the business grows, they may incorporate a limited liability company. They could even set up a family trust to hold the company shares, allowing income to be split between them and their adult children who work in the cafe. By getting the structure right and keeping business and family arrangements clear, this family can enjoy the convenience of working together while reaping financial benefits and protecting their assets. Each family business will have its own journey, but careful planning and open communication are universally helpful in turning a family venture into a lasting success story.

Legal essentials and family governance

Running a family business professionally means putting proper legal frameworks in place. Formal agreements are crucial – document roles, ownership and decision-making processes clearly. If you have multiple family co-owners, set up a partnership or shareholders’ agreement to spell out each person’s role, decision-making authority, and what happens if someone exits. This helps prevent disputes by addressing issues such as retirement or strategic disagreements before they arise.

Set clear boundaries between family and work. Personal issues can easily spill into the business if not managed, so try to keep “shop talk” to work hours (not every family dinner) and make sure everyone understands their role in the business. Good communication is key—clarify expectations and ensure everyone feels heard.

Bring in outside talent or advisors when needed– a non-family perspective can fill skill gaps and reduce insular decision-making. Treat family and non-family staff equally and professionally to avoid any perception of nepotism. An external mentor or even a small advisory board can also help keep your business on track objectively.

Example: Australia has many enduring family businesses that chose their structures wisely. Haigh’s Chocolates, for instance, has remained a privately held family company since 1915 and is now led by the fourth generation of the Haigh family. Another iconic example is Coopers Brewery, founded in 1862, which is still family-run after six generations of Coopers at the helm. These companies show that getting the foundations right and planning for the long term can build a legacy.

Accounting, finances and tax compliance

Sound financial management keeps your family business healthy. First, keep business finances separate from personal finances—open a dedicated business bank account and avoid using it for personal expenses. This makes bookkeeping easier and is viewed favourably by the ATO. Consider using accounting software or a bookkeeper to track income and expenses, manage cash flow, and ensure bills and taxes are paid on time. Staying on top of the books also helps maintain harmony, because financial surprises or unpaid debts can strain family relationships.

If you employ family members, treat them like any other employees for legal and tax purposes. This means:

- Pay legal wages at least the minimum award rate, and make superannuation contributions.

- Keep proper records of their work – timesheets and employment contracts.

- Avoid artificial arrangements – don’t pay family who do no real work, or pay inflated wages just to reduce tax. The ATO monitors such practices and can deny deductions.

One benefit of hiring family is that you may spread income around. For example, a lower-earning spouse or an older teenager on the team can earn up to the tax-free threshold (about $18,200) and pay no income tax – while your business still claims a deduction for their wages. Just ensure any family member in the business is actually contributing and being paid fairly for what they do.

Stay on top of tax compliance

Lodge your BAS and tax returns on time, and meet payroll reporting requirements. Remember that qualifying small companies pay a lower 25% company tax rate, and if you use a trust, follow the rules for distributing income to family members properly. An accountant can help you navigate issues like fringe benefits tax and ensure you’re getting any small-business tax concessions available.

Planning for succession and long-term success

Plan for succession early – many experts recommend starting handover plans at least 3–5 years in advance. Talk openly with your children or other potential successors about their interests. Don’t assume they’ll automatically want to take over. If not all your kids want to be involved, figure out a fair way to treat those who aren’t.

Gradually prepare the next generation by increasing their responsibilities and mentoring them. Decide how and when you will hand over leadership and ownership – whether you step back slowly or retire outright. Every family is different – some transitions are smooth, others are emotionally charged. An independent advisor can help guide tough conversations, and professional advice will ensure the transition is structured correctly.

Conclusion

Running a small-to-medium family business is a balancing act between family and commerce. By setting up the right legal structure, keeping solid accounts, staying on top of tax obligations, and planning for growth and succession, you set the stage for lasting success. Remember to communicate openly and seek professional advice when needed – accountants, tax agents and lawyers (who often advise many family businesses) can provide invaluable guidance. With passion, planning and a bit of patience, your family business can not only support your household today but also become a proud legacy for future generations. Good luck with your family business journey!