Practice Update July 2025

Shila is taking the leap

Shila is 58. She has worked for an engineering firm for 13 years and earns decent wages. Shila would like to work for a few more years but has yet to achieve her full potential. She certainly adds value to her role.

Her employer, No-mans-project, has been experimenting with AI-driven process optimisations for a few years and is now ready to implement the new processes. Unfortunately, implementing the new process means some redundancies, and Shila is one of the staff members who has been proposed to review a redundancy proposal.

Shila is now at a crossroads with her thoughts of retirement, staying in the workforce for a few more years with a new employer or taking a pay cut with the current employer for a different role. Her superannuation preservation age is 60, which is not too far away.

Let’s guide Shila through a few options, with some analysis and pros and cons.

Shila takes the redundancy

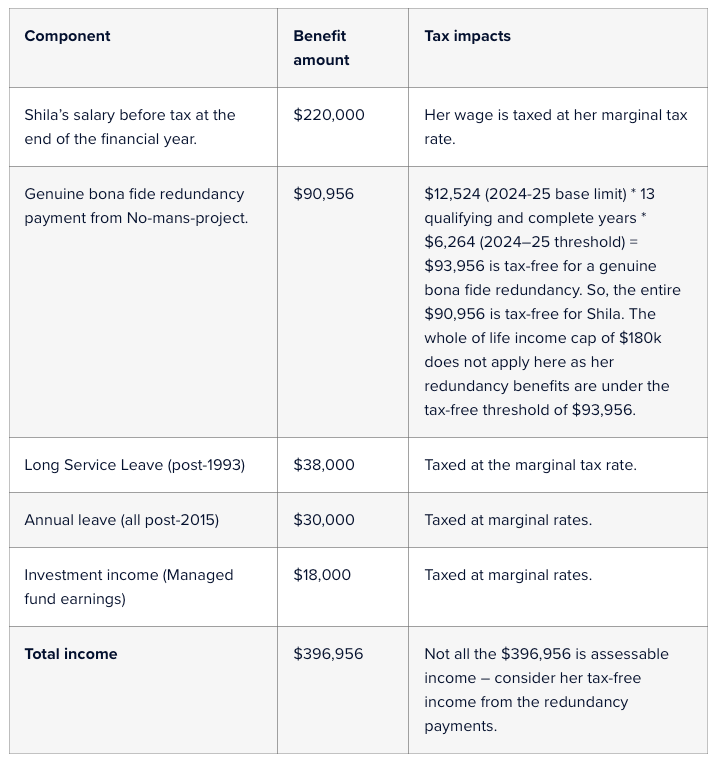

Let’s first find out her assessable income at the end of the financial year when the redundancy benefits are considered.

Shila’s assessable income if she takes the redundancy

Shila’s assessable income for the financial year (based on the above facts) if she takes the redundancy is –

Wage = $220,000

Long service leave payout = $38,000

Annual leave benefit = $30,000

Investment income = $ 18,000

Total assessable income = $ 306,000

Shila’s options with the after-tax money

Assume Shila paid X amount of tax this year on her assessable income. So, she is left with $396,956- X amount to plan her next step. Note that Shila has not reached her superannuation preservation age, which is 60 for her.

Superannuation contribution

Shila may consider contributing a significant part of the benefits to her superannuation account as a non-concessional contribution and may utilise the non-concessional contribution bring-forward limits. The bring forward rule allows the equivalent of 1 or 2 years of annual cap from future years.

This means she can contribute up to 2 or 3 times the annual cap amount in the first year of the bring-forward period. For 2024-25, the non-concessional contribution cap is $120k. This means Shila can make a non-concessional contribution of up to $120k*3=$360k this financial year, assuming she has not utilised the bring forward cap before. Shila must also consider her Total Superannuation Balance (TSB) cap ($1.9 million from 2023/24) to determine how much non-concessional contributions can be made. Also, Shila is 58 (a long way from age 67), so she does not need to meet the work test to make her non-concessional contribution.

Shila can consider this avenue if she does not need to access much cash for other purposes immediately. Also, note that Shila is only two years away from age 60, when she can access her superannuation benefits without paying withdrawal tax if she stays retired.

Other choices

Of course, Shila can pursue other choices. These include investing outside the superannuation environment, paying off a mortgage or other debts, and planning to return to a part-time or full-time job immediately or in the near future.

What does Shila do?

Shila’s kids are grown up, and her mortgage is nearly done. She’s been thinking about consulting or part-time project work anyway.

“I’m not rushing back into a 9–5. I might take six months off, maybe do a few contracts or take on a board gig.”

This offers her a buffer to breathe and rethink life, time to upskill, pivot or semi-retire and some solid super balance to fall back on. Shila decides to get a part-time job from July 1 next year, so her redundancy payout doesn’t push her into a higher tax bracket this year when her part-time wages are included.