Practice Update June 2025

Key concerns when selling a business in: A strategic guide for business owners

Selling a business is one of the most significant decisions a business owner will ever make. Whether a long-standing family operation or a recently scaled-up enterprise, the process requires detailed planning, expert advice, and a sharp understanding of the tax, legal, and commercial landscape. This article explores the most pressing concerns for business owners preparing for a sale, focusing on structural readiness, tax optimisation, timing, and macroeconomic or industry-specific influences.

Business structure and sale readiness

Is your business sale-ready?

Many business owners operate under structures that suit them initially—sole trader, partnership, trust, or private company—but may not be optimal when it’s time to exit. Buyers prefer simplicity and legal clarity; complex structures can introduce unnecessary friction during due diligence.

Example:

A logistics company structured as a discretionary trust with multiple beneficiaries found buyer interest waning due to the convoluted ownership model. When the business was restructured into a clean corporate entity with defined shareholdings, it was sold within six months.

So, align your structure with buyer expectations, often a company limited by shares with clear asset ownership and tax history, at least 2–3 years before planning a sale.

Clean up the balance sheet

Buyers scrutinise assets and liabilities closely. Loans to shareholders, non-core assets, or related-party transactions can muddy the waters.

Steps to Take:

- Repay or eliminate shareholder loans.

- Write off obsolete inventory.

- Dispose of redundant or non-performing assets.

- Finalise ongoing disputes or litigation, if possible.

Tax planning: Unlocking value and minimising liability

Understanding the Capital Gains Tax (CGT) Landscape

CGT is typically the most substantial tax liability when a business is sold. There are several small business CGT concessions, which, if used correctly, can eliminate or significantly reduce tax payable.

The key CGT concessions:

- 15-year exemption: No CGT if you’ve owned the business for 15 years, are over 55, and are retiring.

- 50% active asset reduction: Halves the capital gain on active business assets.

- Retirement exemption: Up to $500,000 of capital gains can be tax-free if contributed to superannuation.

- Rollover relief: Defer gains when selling one business and buying another.

Example:

A software consultancy qualified for the 15-year exemption by ensuring the shares were held by an individual over 55 and that the asset was active. Their $2.8M sale was completely CGT-free.

Important consideration:

These concessions are complex. Eligibility hinges on factors like asset use, ownership periods, turnover thresholds ($2M for some rules, $6M net asset test for others), and even the specific structure of the entity. Engage an experienced accountant early.

Trust distributions and Div 7A implications

If your business is structured using a trust or company, unpaid distributions or loans to beneficiaries/shareholders could trigger Division 7A implications, which would tax these as unfranked dividends.

Action items:

- Ensure trust distributions are documented and paid.

- Review shareholder loans and ensure that repayments or compliant loan agreements exist.

GST and stamp duty

- GST: Business sales can be GST-free under the ‘going concern’ exemption if the buyer continues the business.

- Stamp duty: While not always applicable, certain states (e.g., NSW, VIC) impose stamp duty on business asset sales.

Timing the sale: Market, tax year, and life events

Timing within a tax year

Selling in June versus July can significantly impact your personal tax return. Deferring a sale into a new financial year can provide more time to prepare, structure super contributions, or even allow a better tax planning window.

Case in point:

A café sold in late June 2024, leaving the owners little time to implement superannuation strategies or prepay expenses. A sale just weeks later in July could have reduced their overall tax bill.

Economic and industry cycles

Industry multiples fluctuate with economic confidence, legislative changes, and media narratives. Selling into a buyer’s market (high demand for acquisitions) can significantly improve valuations.

Example:

Childcare businesses saw a surge in private equity interest in 2022, driven by government subsidies and market consolidation trends. Owners who sold then realised 7–9x EBITDA multiples, versus 4–5x just three years earlier.

Retirement and Health Planning

Many owners delay sale decisions, only to be forced to exit suddenly due to health issues or burnout. Several years out, planning the sale gives flexibility to negotiate, reduce tax, and groom a successor or key employee.

Accounting and financial housekeeping

Normalising earnings

Buyers assess businesses based on ‘normalised EBITDA’ — earnings adjusted for one-off items, owners’ personal expenses, or non-recurring revenue/costs.

Action plan:

- Cease running personal expenses through the business.

- Identify and document add-backs transparently.

- Remove reliance on key individuals, including the owner.

Updated financials and forecasting

Buyers will want:

- The last three years of accountant-prepared financials.

- Year-to-date management reports.

- Forecasts showing future growth potential.

Best practice:

Work with your accountant to ensure accrual-based records, aged receivables/payables, and reconciled accounts. Sloppy or unclear financials may delay the deals.

Due diligence preparation

Create a virtual data room and include:

- Tax returns (company/trust/individual) for 3–5 years.

- Copies of key contracts (leases, supplier agreements, employment contracts).

- Asset register.

- IP and domain ownership records.

Tip:

Conduct your own “vendor due diligence” before going to market, identifying red flags before a buyer finds them.

Legal and regulatory compliance

Contracts, IP, and licences

Ensure all contracts are:

- In the business name (not a personal name).

- Assignable to a buyer.

- Current and signed.

Check that:

- Trademarks and domain names are registered and owned by the business.

- Any government or industry licences are up to date.

Employment law

Employee entitlements (long service leave, annual leave, redundancy, etc.) must be adequately accounted for. Some buyers will require the seller to pay out entitlements at settlement.

Modern award compliance is another flashpoint. In 2020, several hospitality businesses were involved in underpayment scandals that stalled sales and required rectification.

Data and privacy laws

This is especially relevant for tech businesses, but applies to any business holding customer data. New Australian privacy reforms (proposed to strengthen penalties and compliance obligations as of 2024) may increase buyer concern over potential liabilities.

Technological, legislative and industry trends

The impact of AI and automation

Businesses that embrace tech (e.g., CRM systems, cloud accounting, and inventory tracking) are more efficient and attractive to buyers.

Example:

Two regional veterinary practices went to market in 2023. One had paper-based systems and poor records; the other had cloud-based software, automated appointment reminders, and centralised records. The second sold for 20% more.

ESG and sustainability

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices are increasingly a factor in private equity and institutional buyer decisions. Sustainable sourcing, low emissions, and fair wages can all boost valuation or widen the pool of buyers.

Changes in law

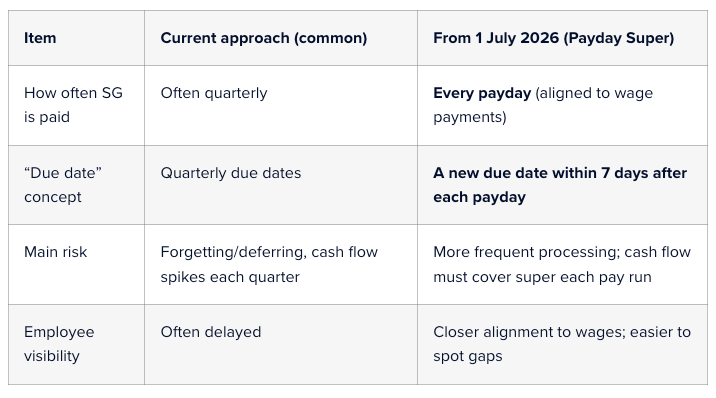

Upcoming legal reforms — such as changes to superannuation contribution caps, company director identification rules, and increased enforcement by the ATO and ASIC can affect how you prepare for a sale.

For instance:

The 2025 tightening of Division 293 superannuation tax thresholds may make super contributions less attractive for high-income earners, shifting some tax planning strategies in the lead-up to sale.

Emotional and legacy concerns

Letting go

Many owners underestimate the emotional weight of selling a business, especially one built over decades. This can lead to overvaluation, second-guessing, or dragging out the process.

Family and Succession

If a family member buys or takes over the business, considerations shift to fairness, estate planning, and possibly staged handovers or vendor financing.

Example:

An agribusiness in regional NSW was sold to the owner’s son at a discounted valuation with a five-year earn-out and coaching period. The structure maintained harmony while allowing a generational shift.

Practical steps to take now

- Engage a tax adviser and lawyer 2–3 years before your intended sale.

- Get a business valuation to understand what your business is worth today — and what you can do to increase that.

- Groom a second-in-command to de-risk the business from key person dependency.

- Develop a buyer profile: Is your ideal buyer a competitor, private equity investor, a customer, or a family member?

- Start thinking about life after the sale. Retirement, philanthropy, consulting, or a new business?

Selling a business is a multi-faceted process beyond finding a buyer. It requires careful tax planning, legal and operational grooming, industry awareness, and emotional readiness. The sooner you start preparing, the more likely you will walk away with a higher valuation, a smoother process, and a legacy you can be proud of.

No two exits are the same. But with the proper preparation, expert guidance, and awareness of your business’s strengths and weaknesses, you can turn a potentially stressful transition into a strategic success.