Practice Update April 2025

A foreign entrepreneur’s guide to starting a business in Australia

Starting a business as a foreign entrepreneur can be an exhilarating way to access new markets, diversify investment portfolios, and create fresh opportunities. Many countries around the globe provide pathways for non-residents and foreign nationals to register businesses. However, understanding different countries’ legal requirements, procedures, and opportunities is crucial for success. In this issue, we will navigate the process of establishing a business in Australia to help foreign entrepreneurs looking to register a company in Australia.

Key takeaways

- Foreign entrepreneurs can fully own Australian businesses with no restrictions on ownership.

- Registered office and resident director requirements are key legal considerations.

- ABN and ACN are essential for business registration.

- The application process can be done online, simplifying the process for foreign entrepreneurs.

Why register a business as a foreign entrepreneur?

There are various reasons why a foreigner may want to register a company in another country. These reasons include expanding into a foreign market, taking advantage of favourable tax laws, leveraging local resources, or benefiting from business-friendly regulatory environments.

Before registering, conducting thorough market research to assess whether establishing a business abroad aligns with your objectives is essential. Understanding the country’s political and economic climate, legal framework, and tax system will help ensure the success of your venture.

The general process for registering a business as a foreign entrepreneur

While the exact requirements may differ from country to country, some common steps apply to most jurisdictions when registering a company as a foreign entrepreneur:

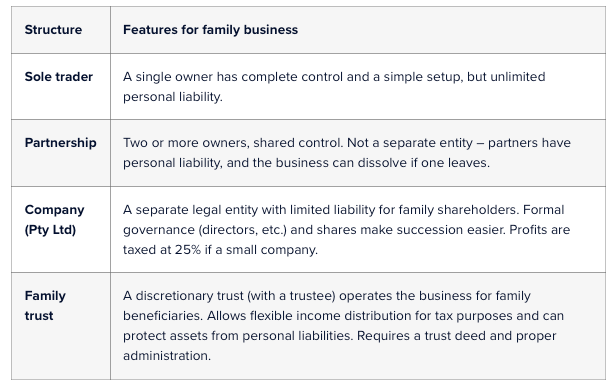

Choosing the business structure

The first step is deciding on the appropriate business structure. The structure determines liability, taxation, and governance. Common types of business structure include:

- Sole proprietorship: A single-owner business where the entrepreneur has complete control and entire liability.

- Limited Liability Company (LLC): Offers liability protection to the owners, meaning their assets are not at risk.

- Corporation (Inc.): A more complex structure that can issue shares and offers limited liability to its shareholders.

Different countries have varying rules regarding foreign ownership, so understanding the options available is essential before registering a company.

Registering with local authorities

Regardless of the jurisdiction, most countries require you to register your company with the relevant local authorities. This process typically includes submitting documents such as:

- Company name and business activities: You need to choose a unique company name that adheres to local naming regulations.

- Articles of incorporation: This document outlines the company’s structure, activities, and bylaws.

- Proof of identity: As a foreign entrepreneur, you will likely need to provide a passport and other identification documents.

- Proof of address: Many countries require a physical address for the business, which may be the address of a registered agent or office.

Tax Identification Number (TIN) and bank accounts

After registering the company, you will typically need to apply for a tax identification number (TIN), employer identification number (EIN), or equivalent, depending on the jurisdiction. This number is used for tax filing and reporting purposes.

Opening a business bank account is another critical step. Some countries require a local bank account for business transactions, and you may need to visit the bank in person or appoint a local representative to help with the process.

Complying with local regulations

Depending on the type of business, specific licenses and permits may be required to operate legally. For example, food service, healthcare, or transportation companies may need specific licenses. Compliance with local labour laws and intellectual property protections may also be necessary.

Appoint directors and shareholders

To register a company, you’ll need to appoint at least one director who resides in Australia. The director will be responsible for ensuring the company meets its legal obligations. You will also need to appoint shareholders, who can be either individuals or corporations.

For foreign entrepreneurs, the requirement for a resident director is one of the key challenges. If you don’t have a trusted individual in Australia to act as the director, you can engage a professional service to fulfil this role. This ensures your business remains compliant with local regulations.

Choose a company name

Next, you need to choose a company name. The name should reflect your business but must be unique and available for registration. You can check the availability of a name through the Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC) website.

Remember that the name must meet legal requirements and cannot be similar to an existing registered company. If you’re unsure, seeking professional advice is always a good move.

Apply for an Australian Business Number (ABN) and Australian Company Number (ACN)

Once you’ve selected your business structure and appointed your directors, it’s time to apply for an Australian Business Number (ABN) and an Australian Company Number (ACN). These are essential for running your business in Australia.

- ABN: This unique 11-digit number allows your business to interact with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) and other government agencies.

- ACN: This 9-digit number is allocated to your company upon registration with ASIC and serves as your business’s unique identifier.

You can easily apply for both numbers online through the Australian Business Register (ABR) and the ASIC websites.

Register for Goods and Services Tax (GST)

If your business expects to earn more than $75,000 in revenue annually, you must register for GST. This means your business will charge customers an additional 10% on goods and services. The GST registration threshold for non-profit organisations is higher at $150,000 annually. If your company is below these thresholds, registering for GST is optional, but registration becomes mandatory once it exceeds the limit.

Set up a registered office

Every Australian company must have a registered office in Australia. This is where all official government documents, including legal notices, are sent. You can use your premises or hire a foreign company registration service to provide a virtual office address.

Common challenges for foreign entrepreneurs

While the process is relatively simple, there are a few hurdles that foreign entrepreneurs may encounter when registering a company in Australia:

- Resident director requirement: You’ll need a director residing in Australia. If you don’t have one, you’ll need to engage a service provider to fulfil this role.

- Understanding local tax laws: Australia has a corporate tax rate of 25% for small businesses with annual turnovers of less than $50 million. However, larger companies with turnovers exceeding $50 million are subject to a standard corporate tax rate of 30%. Foreign entrepreneurs must also understand the implications of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and payroll tax.

- Compliance with Australian regulations: Navigating Australia’s various regulations and compliance requirements can be time-consuming. An accountant or adviser can help you in this regard.

FAQs

- Can I register a company in Australia as a foreigner?

- Yes, foreign entrepreneurs can register a company in Australia. The only requirement is to have a resident director.

- Do I need to be in Australia to register a company?

- No, you can complete the registration process online. However, you must appoint a resident director.

- Do I need an Australian bank account to start a business in Australia?

- You will need an Australian bank account to handle your business’s finances and transactions.

- Can I operate my Australian company from abroad?

- Yes, you can operate your company remotely, but you must comply with all local tax laws and regulations.