Practice Update September 2025

Land tax in Australia: exemptions, tips and lessons

Land tax is one of those quiet state-based taxes that does not grab headlines like income tax or GST, but impacts property owners once thresholds are crossed. It applies when the unimproved value of land exceeds a certain amount, which differs from state to state. Principal places of residence are usually exempt, but investment properties, commercial holdings, and certain rural blocks may be subject to taxation.

For individuals and small businesses, land tax is worth paying attention to because exemptions can make the difference between a manageable annual bill and a nasty surprise. A recent case in New South Wales (Zonadi case) has sharpened the focus on when land used for cultivation qualifies for the primary production exemption. The lessons are timely for farmers, winegrowers and anyone with mixed-use rural land.

The basics of land tax

Each state and territory (except the Northern Territory) imposes land tax. Key features include:

- Assessment date: Usually determined at midnight on 31 December of the preceding year (for example, the 2026 assessment is based on ownership and use as at 31 December 2025).

- Thresholds: Vary across jurisdictions. For example, in 2025, the NSW threshold is $1,075,000, while in Victoria it is $300,000.

- Exemptions: Principal place of residence, primary production land, land owned by charities and specific concessional categories.

- Rates: Progressive, with higher landholdings paying higher rates.

Unlike council rates, which fund local services, land tax is a revenue measure for states. It is payable annually and calculated on the total taxable value of landholdings.

Primary production exemption

Most states exempt land used for primary production from land tax. The policy aim is precise: farmers should not be burdened with land tax when using their land to produce food, fibre or similar goods. However, the details of what constitutes primary production vary.

Qualifying uses generally include:

- cultivation (growing crops or horticulture)

- maintaining animals (grazing, dairying, poultry, etc.)

- commercial fishing and aquaculture

- beekeeping

Sounds straightforward, but the catch is in how the land is used and for what purpose.

Lessons from the Zonadi case

The Zonadi case involved an 11-hectare vineyard in the Hunter Valley. The land was used for:

- 4.2ha of vines producing wine grapes

- a cellar door and wine storage area

- a residence and tourist accommodation

- some trees, paddocks and access ways

During five land tax years in dispute, the taxpayer sold some grapes directly but used most of the crop to make wine off-site, which was then sold through the cellar door. Income was derived from grape sales, wine sales and tourist accommodation.

The NSW Tribunal had to decide whether the land’s dominant use was cultivation for the purpose of selling the produce of that cultivation (a requirement under section 10AA of the NSW Land Tax Management Act).

The outcome was a blow for the taxpayer. The Tribunal said:

- Growing grapes was indeed a form of cultivation and amounted to primary production.

- But cultivation for the purpose of making wine did not qualify, because the exemption only applies where the produce is sold in its natural state. Wine is a converted product, not the product of cultivation.

- Although some grapes were sold directly, the bulk of the financial gain came from wine sales.

- Therefore, the dominant use of the land was cultivation to make and sell wine, which is not exempt.

The exemption was denied, and the taxpayer was left with a land tax bill.

Why this matters

For small businesses, especially those that combine farming with value-adding activities such as processing or tourism, the case serves as a warning. The line between primary production and secondary production can determine whether a land tax exemption applies.

If most income comes from a cellar door, farmstay, or product manufacturing, the exemption may be at risk, even though cultivation is occurring on the land.

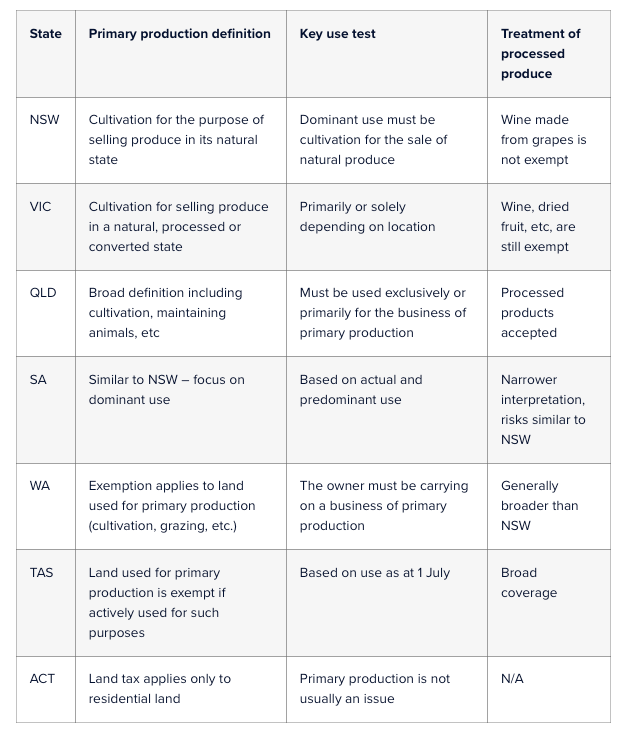

Different rules in Victoria

Victoria takes a broader view. It defines primary production to include cultivation for the purpose of selling the produce in a natural, processed or converted state. In other words, grapes sold for wine production would still be considered primary production.

The only further hurdle is the “use test”, which depends on location:

- outside Greater Melbourne: land must be used primarily for primary production

- within urban zones: land must be used solely or mainly for the business of primary production

Had Zonadi been in Victoria, the outcome could have been very different. The vineyard would likely have been exempt from this requirement.

State-based comparisons

Here’s a snapshot of how land tax treatment differs across states when it comes to cultivation and primary production:

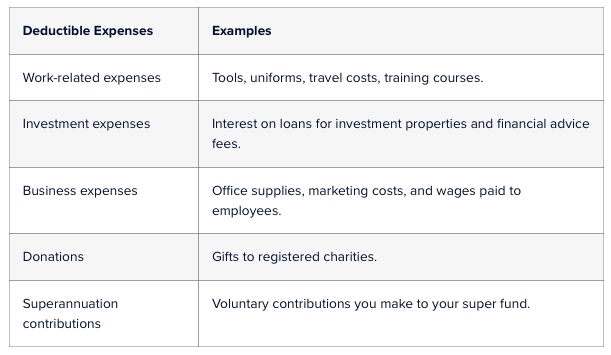

Tips and strategies for individuals and small businesses

- Understand the dominant use test

In NSW and SA, revenue authorities look at all uses of the land. If tourist accommodation or value-added services are the primary source of revenue, the exemption may be denied. - Document use and income streams

Keep records showing the proportion of land used for cultivation, time and labour spent, and income split between activities. This evidence can be crucial if challenged. - Consider state differences

If you own land in multiple states, be aware of the differences in laws and regulations. Victoria and Queensland are generally more generous in recognising processed or converted products as primary production. - Review structures

Using trusts or companies can change liability, but exemptions are tied to use, not ownership structure. Ensure your entity is eligible. - Timing matters

Use is assessed at a specific date (e.g., 31 December in NSW). Authorities may examine use in the months before and after, so seasonal activities should be well-documented. - Beware of mixed uses

Combining a farm with accommodation or hospitality may tip the balance. If non-farming income grows, land tax bills may also increase.

Conclusion

Land tax in Australia can be a complex and patchwork-like system. For individuals and small businesses, particularly those in farming and agribusiness, the rules surrounding the primary production exemption are crucial. The Zonadi case illustrates the fine line between cultivation for sale in its natural state and cultivation that feeds into a processing business.

The main lessons are:

- In NSW and SA, be cautious if most of your income comes from processed products, such as wine, cheese, or farmstay tourism.

- In Victoria and Queensland, the rules are more forgiving, recognising processed or converted products.

- Documenting use, income and labour is essential if challenged.

For small landholders, a clear-eyed view of how their land is actually used and where the money comes from can save costly disputes. And if in doubt, get advice early, because once the Commissioner issues a land tax assessment, the burden is on you to prove you qualify for the exemption.