IMPACTS OF THE REVISED STAGE 3 PERSONAL TAX CUTS

IMPACTS OF THE REVISED STAGE 3 PERSONAL TAX CUTS

Summary of the changes to the tax brackets and tax rates

On 27 February 2024, Parliament passed the Treasury Laws Amendment (Cost of Living Tax Cuts) Bill 2024 (the Bill) containing the Government’s revisions to the Stage 3 personal tax cuts, which take effect from the 2024–25 financial year. At the time of writing, the Bill is awaiting Royal Assent.

This article summarises the changes to the tax brackets and tax rates and illustrates the potential implications for taxpayers with a range of taxable incomes. The Government will also increase the Medicare levy low-income thresholds for 2023–24. This article will not cover this proposed change.

From 1 July 2024, the revised Stage 3 tax cuts will:

- reduce the 19% tax rate to 16%

- reduce the 32.5% tax rate to 30%

- Increase the threshold above the 37% tax rate from $120,000 to $135,000.

- Increase the threshold above the 45% tax rate from $180,000 to $190,000.

There will be no change to the current tax-free threshold of $18,200 or $416 on eligible income under the taxation of minor rules. No taxpayer will pay more tax than that which would apply under the 2023–24 rates, but higher-income taxpayers will receive a lower tax cut than under the previous Stage 3 plan.

Taxpayers with taxable incomes up to $45,000 will benefit from a reduction of their marginal tax rate from 19 per cent to 16 per cent (maximum tax saving of $804). Under the previous Stage 3 plan, there was no change to the current (2023–24) tax bracket ($18,201 to $45,000) or marginal tax rate (19 per cent).

Middle-income taxpayers will receive an extra tax cut of $804 (on top of the tax cut they would have received under the previous plan).

The benefit of the changes (in comparison to the previously legislated Stage 3 plan) cuts out at taxable incomes of approximately $147,000 — taxpayers at this income level will be $36 worse off under the changes (albeit with a saving of $3,729 from 2023–24 rates).

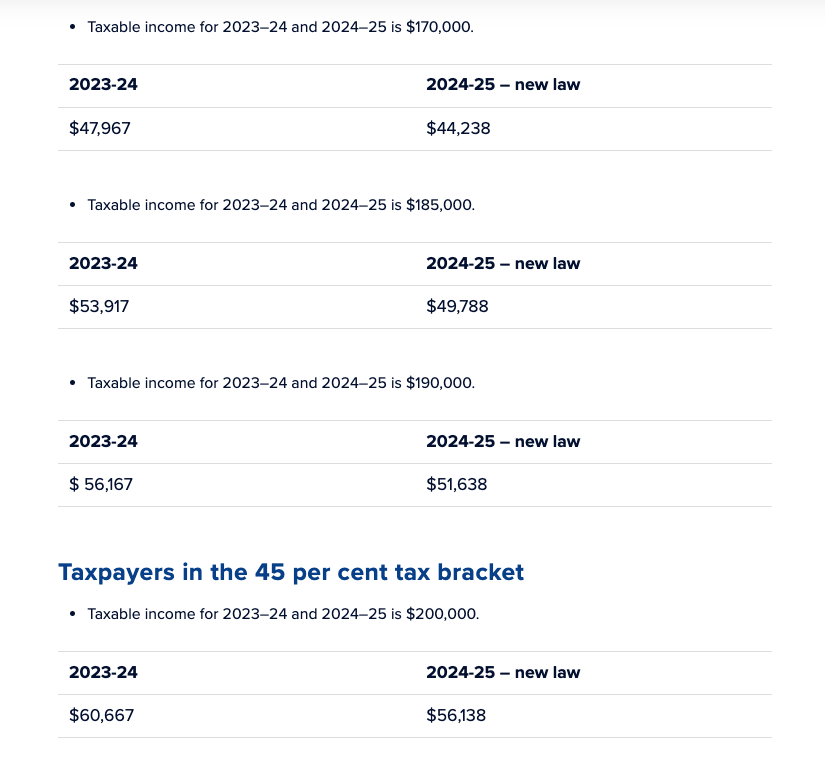

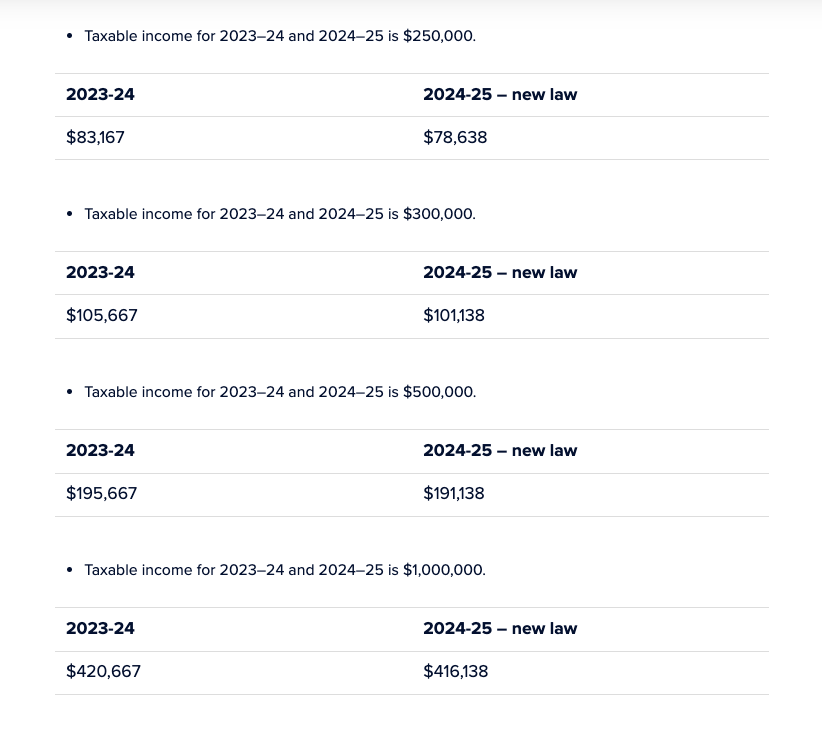

For taxpayers with taxable incomes of $200,000 and above, the tax cut will be worth $4,529 instead of $9,075 — i.e. the Stage 3 benefit will be cut by half.

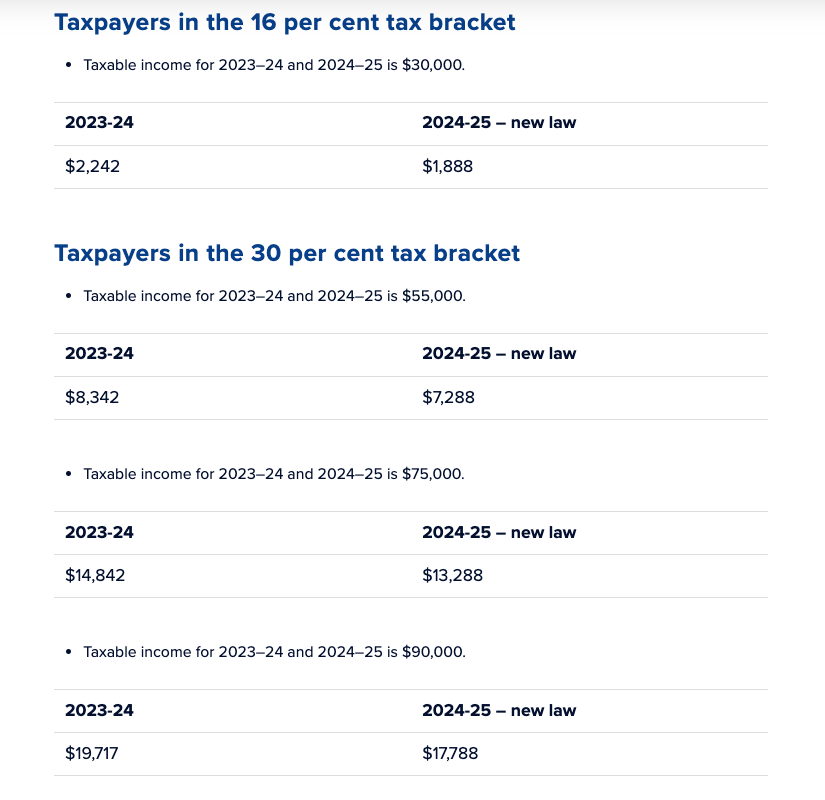

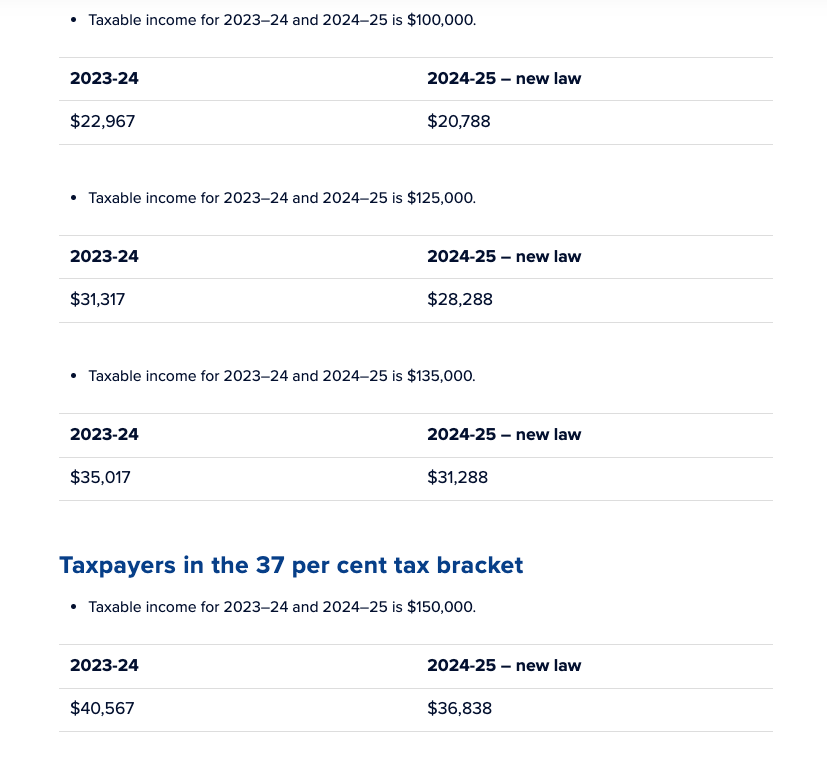

How the changes will affect resident taxpayers

The following examples set out the tax liability for a given taxable income under the current (2023–24) tax rates and the revised Stage 3 rates from 2024–25. Assume that each taxpayer’s taxable income is the same in 2023–24 and 2024–25.

Note that the Treasury’s tax cut calculator considers the basic tax scales, low-income tax offset (as applicable) and the Medicare levy. The following illustrative examples only consider the basic tax rates. Therefore, the outcomes from the Treasury’s calculator will not be the same as what is represented below.