Practice Update November 2018

P r a c t i c e U

p d a t e

November 2018

Fast-tracking tax cuts for small and medium businesses

The Government has fast-tracked the already legislated tax cuts to small and medium businesses by bringing them forward five years .

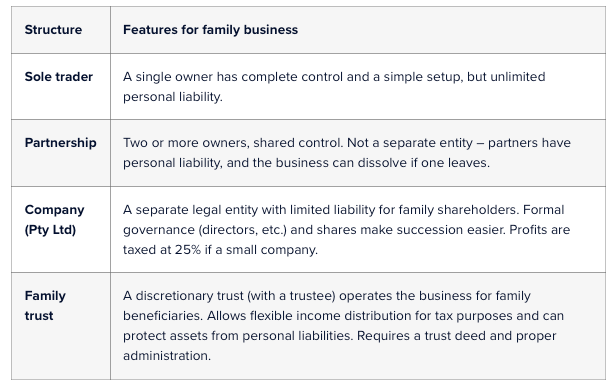

Companies with an aggregated turnover of less than $50 million will have a tax rate of 25% in the 2022 income year (instead of the 2027 income year based on the previously legislated timeline).

Similarly, the increase in the tax discount to 16% for unincorporated entities will apply from the 2022 income year , rather than the 2027 income year.

Editor: Small and medium businesses will appreciate the earlier access to the already legislated tax cuts.

Proposed expansion of STP to smaller employers

Single Touch Payroll (‘STP’) commenced on 1 July 2018 for approximately 73,000 employers who have 20 or more employees.

There is currently legislation before Parliament to expand STP to all employers from 1 July 2019 and it is estimated that there will be more than 700,000 employers who will enter STP as a result.

Even though the proposed expansion is not yet law, the ATO recommends that smaller employers consider voluntarily opting-in to STP early.

The ATO acknowledges there is a large number of very small employers who have less than five employees (‘micro-employers’) who do not currently use a payroll product and has indicated that they are not looking to force them to take up a product to do STP.

Efforts are being made to work with industry to look at some alternate reporting mechanisms.

It is being reported that software developers, and even some of the larger banks, have shown an interest in developing some kind of product that would enable micro-employers to provide the necessary data to comply with STP at a low cost.

Employers who are in an area that has internet issues or challenges are reminded that there are potential exemptions available under STP.

The ATO is currently consulting with focus groups to look at flexible options to transition micro-employers to STP over the next couple of years.

Assuming the relevant legislation passes, the ATO does not realistically expect that everyone will start STP from 1 July 2019 and has indicated that it will be flexible with the commencement date, including the provision of deferrals to help stagger the uptake.

Editor: This is a very positive message from the ATO, particularly for micro-employers.   Hopefully, together with the relevant software developers, they are able to come up with a low-cost and simple alternative for those who do not currently use payroll software to comply with their STP obligations.

Expansion of the TPRS

The Taxable Payments Reporting System (‘TPRS’) has been expanded to the cleaning and courier services industries from 1 July 2018 .

Businesses that have an ABN and make any payments to contractors for cleaning or courier services provided on behalf of the business must lodge a Taxable Payments Annual Report (‘TPAR’) each income year.

The first TPAR for payments made to contractors from 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2019 will be due by 28 August 2019 .

Where cleaning or courier services are only part of the services provided by the business, they will need to work out what percentage of the payments they receive are for these services each income year to determine if a TPAR is required to be lodged.

Specifically, if the total payments the business receives for the relevant services are:

q 10% or more of their GST turnover – a TPAR must be lodged.

q Less than 10% of their GST turnover – a TPAR is not required to be lodged, but the business can choose to lodge one.

Ban on electronic sales suppression tools

From 4 October 2018 , the Government has banned activities involving electronic sales suppression tools (‘ESSTs’) that relate to people or businesses that have Australian tax obligations.

The production, supply, possession or use of an ESST (or knowingly assisting others to do so) may attract criminal and administrative penalties.

ESSTs can come in different forms and are constantly evolving, some examples include:

q An external device connected to a point of sale (‘POS’) system.

q Additional software installed into otherwise-compliant software.

q A feature or modification that is a part of a POS system or software.

An ESST may allow income to be misrepresented and under-reported by:

q deleting transactions from electronic record-keeping systems;

q changing transactions to reduce the amount of a sale;

misrepresenting sales records (e.g., by allowing GST taxable sales to be re-categorised as GST non-taxable sales); or

q falsifying POS records.

Transitional arrangements are in place for six months starting from 4 October 2018 to 3 April 2019 for possessing an ESST.

Taxpayers may avoid committing an offence for possessing an ESST if they:

q acquired it before 7:30pm 9 May 2017; and

q advise the ATO that they possess the tool.

Importantly, the transitional provisions do not apply to the manufacture, development, publication, supply or use of an ESST.

Depending on the offence and severity of the crime, taxpayers can face financial penalties of up to 5,000 penalty units, which currently equates to over $1 million.

Scammers impersonating tax agents

The ATO has received increasing reports of a new take on the ‘fake tax debt’ scam, whereby scammers are now impersonating registered tax agents to lend legitimacy to their phone call.

The fraudsters do this by coercing the victim into revealing their agent’s name and then initiating a three-way phone conversation between the scammer, the victim, and another scammer impersonating the victim’s registered tax agent or someone from the agent’s practice.

As the phone conversations with the scammers appeared legitimate and the victims trusted the advice of the scammer ‘tax agent’, victims have been falling for this new approach.

In a recent example, a victim withdrew thousands of dollars in cash and deposited it into a Bitcoin ATM, fearing that police had a warrant out for their arrest.

The ATO is reminding taxpayers that they will never:

q demand immediate payments;

q threaten them with arrest; or

q request payment by unusual means, such as iTunes vouchers, store gift cards or Bitcoin cryptocurrency.

Taxpayers are advised that if they are suspicious about a phone call from someone claiming to be the ATO, then they should disconnect and call the ATO or their tax agent to confirm the status of their tax affairs and verify the call.

Please Note: Many of the comments in this publication are general in nature and anyone intending to apply the information to practical circumstances should seek professional advice to independently verify their interpretation and the information’s applicability to their particular circumstances.