Personal super contribution and deductions

Personal super contribution and deductions

In this issue, we discuss how to make personal super contributions, including claiming a tax deduction to make them concessional contributions.

What are personal super contributions?

You can boost your super fund by adding your personal contributions, which are the amounts you contribute directly to your super fund. If you claim a tax deduction, they’re concessional contributions effective from your pre-tax income. They are taxed in the fund at a rate of 15% unless you have an adjusted taxable income of $250,000.

They’re non-concessional contributions from your after-tax income or savings if you don’t claim a tax deduction. They are not further taxed.

Personal contributions:

are in addition to any compulsory super contributions your employer makes on your behalf

do not include super contributions made through a salary-sacrifice arrangement.

Personal contributions are subject to the contributions caps that apply to concessional and non-concessional contributions.

Concessional contributions cap

The concessional contributions cap is the maximum before-tax contributions you can contribute to your super each year without contributions being subject to extra tax.

- From 1 July 2024, the concessional contributions cap is $30,000.

- From 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2024, the concessional contributions cap for each year was $27,500.

- From 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2021, the concessional contribution cap for each year was $25,000.

The cap increases in increments of $2,500, which aligns with the statistical measure of average weekly ordinary time earnings (AWOTE). If you have unused cap amounts from previous years, you may be able to carry them forward to increase your contribution caps in later years.

Non-concessional contributions cap

The non-concessional contributions cap is the maximum after-tax contributions you can contribute to your super each year without contributions being subject to extra tax.

From 1 July 2024, the non-concessional contributions cap is $120,000. This is now reviewed annually to align with average weekly ordinary time earnings (AWOTE). If you contribute more, you may have to pay extra tax.

Non-concessional contributions caps from 2021–22 onwards.

Financial year Non-concessional cap

2024–25 $120,000

2023–24 $110,000

2022–23 $110,000

2021–22 $110,000

If you make contributions above the annual non-concessional contributions cap, you may be eligible to access future year caps automatically. This is known as the bring-forward arrangement. It allows you to make extra non-concessional contributions without paying additional tax if you meet certain eligibility conditions.

Suppose your total super balance is equal to or more than the general transfer balance cap ($1.7 million from 2021–22, $1.9 million from 2023–24) at the end of the previous financial year. In that case, your non-concessional contributions cap is nil ($0) for the current financial year.

Claiming deductions for personal super contributions

To claim a deduction for your personal super contributions, you must give your super fund a notice in the approved form and get an acknowledgement from the fund. There are other eligibility criteria you must meet.

The personal super contributions you claim as a deduction will count towards your concessional contributions cap. When deciding whether to claim a deduction for super contributions, you should consider the possible impacts, including whether:

- you will exceed your concessional (before-tax) contributions cap, which limits the amount that can be contributed to your super fund that is taxed at the concessional rate of 15%

- you will have to pay Division 293 tax, which applies when your combined income and concessional super contributions for Division 293 purposes are more than $250,000

- you wish to split your contributions with your spouse

- it will affect your super co-contribution eligibility.

If you exceed your cap, you must pay extra tax, and any excess concessional contributions you leave in super will count towards your non-concessional contributions cap.

Example: effects of claiming a deduction for a personal super contribution

From 2019 to 20, Christie will be employed as a hairdresser and earn $35,000 in assessable income.

Christie makes a personal contribution of $5,000 to her super fund. To claim an income tax deduction for the entire contribution, she must give her fund a notice of intent and get an acknowledgement.

Having done this, Christie could claim a tax deduction of $5,000, reducing her taxable income to $30,000. However, her fund would pay a 15% tax on the $5,000, so only $4,250 would be credited to Christie’s super fund account. Additionally, Christie would be eligible for the low-income superannuation tax offset, so the government would refund her offset into her super account. However, she would not qualify for a super co-contribution.

If Christie decided to claim a personal income tax deduction of $4,000 instead of the entire $5,000, this would mean:

- her taxable income would be $31,000

- her fund would have to pay a 15% tax on the $4,000, so $3,400 would be credited to her account

- she may be eligible for the super co-contribution in respect of the $1,000 that was not claimed as a deduction, in which case the government would pay her co-contribution entitlement ($500) into her super account

- she would be eligible for the low-income superannuation tax offset so that the government would refund her offset into her super account.

Work and age restrictions

Suppose you’re under 18 at the end of the income year and you contributed. In that case, you can only claim a deduction for your personal super contributions if you also earned income as an employee or business operator during the year.

If you’re between 67 and 74 years old:

- For the 2020–21 and later years, you must meet the work test (or exemption) to claim a tax deduction for personal contributions and have them treated as concessional contributions.

- From 1 July 2022, you can make or receive non-concessional personal and salary sacrifice contributions without meeting the work test (or exemption). However, you must still meet the work test (or exemption) to claim a deduction for personal superannuation contributions to ensure they are treated as concessional contributions.

If you are 75 or older, you can only claim a deduction for contributions you made before the 28th day of the month following the month you turned 75.

Work test and work test exemption

To satisfy the work test, you must work at least 40 hours during a consecutive 30-day period each income year. However, if you don’t meet the above condition, you can use the exemption to the work test on a one-off basis if you have:

- satisfied the work test in the income year preceding the year in which you made the contribution

- a total super balance of less than $300,000 at the end of the previous income year

- Do not rely on the work test exemption from a previous financial year.

Example: work test to claim a deduction for personal super contributions

In 2021–22, Kumiko turned 66 years old. She did not need to satisfy the work test or meet the work test exemption criteria to claim a deduction for personal super contributions. However, she still had to give her fund a notice of intent and receive an acknowledgement from the fund.

In 2022–23, Kumiko turned 67 years old. Before that, she did not need to satisfy the work test or work test exemption to contribute to her super fund. In that case, she must satisfy the work test or meet the work test exemption criteria to claim a deduction for personal super contributions. She must also continue to provide her fund with a notice of intent and get an acknowledgement from the fund.

Personal super contributions for self-employed

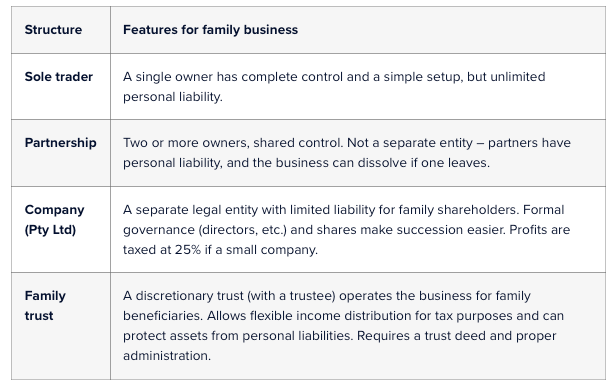

If you’re self-employed as a sole trader or in a partnership, you don’t have to pay a super guarantee for yourself.

You can choose to make personal super contributions to save for your retirement. Make sure your super fund has your tax file number (TFN). If not:

- contributions are taxed an additional 32%

- your fund may not accept personal contributions

- you may miss out on a super co-contribution if you are eligible

- it will be harder to keep track of your super.

You can choose to make personal super contributions from your after-tax income. For example, you can contribute directly from your bank account to your super fund. Most people can claim a tax deduction for personal super contributions until they turn 75. Contributions you make may attract extra tax if they exceed the contribution cap for that year.

Example 1: Self-employed with moderate Income Earner

Scenario:

John’s taxable income is $80,000 in the financial year 2023-24, and he wishes to make personal superannuation contributions to reduce his tax liability.

Key Limits for 2024-25:

- Concessional contributions cap: $30,000 per year.

- Contributions to this cap are taxed 15% within the super fund.

- Non-concessional contributions cap: $120,000 annually (provided the concessional cap is not exceeded).

Step-by-step Calculation:

1.Concessional Contribution:

- John decides to contribute $20,000 as a concessional contribution.

- Tax within the super fund: $20,000 × 15% = $3,000.

- The remaining $17,000 is invested in their super fund.

2.Tax Savings on Income:

- Without contribution, taxable income = $80,000.

- After claiming the $20,000 contribution as a tax deduction, taxable income was reduced to $60,000.

- At a marginal tax rate of 32.5% (plus 2% Medicare levy), the tax saved:

- 20,000 × (32.5%+2%)=20,000×34.5%=6,900

- Net tax saving after considering the 15% tax in the super fund: 6,900−3,000=3,900.

3. Non-Concessional Contribution:

- He also contributes an additional $10,000 as a non-concessional contribution. In year 2024-25, John can contribute this amount as a concessional contribution, being self-employed and also the limit of concessional contribution in 2024-25 is $30,000. In this case, John can get a tax dedution for the extra $10,000 contribution.

- No tax is applied to this contribution within the super fund.

Result:

- John reduces his taxable income to $60,000, saving $3,900 in tax.

- His super fund receives $27,000 ($17,000 concessional + $10,000 non-concessional).

Example 2: Self-employed who has high income

Scenario: Kerry is self-employed and has a taxable income of $200,000 in 2023-24. She wishes to maximise their concessional contributions.

Key Limits for 2024-25:

Concessional contributions cap: $30,000

Additional Division 293 tax (15%) applies for individuals with income over $250,000.

Step-by-step Calculation:

1.Concessional Contribution:

- Kerry contributes the maximum concessional amount of $30,000.

- Tax within the super fund: $30,000 × 15% = $4,500.

- Remaining: $25,500 goes into their super fund.

2.Tax Savings on Income:

- Without contribution, taxable income = $200,000.

- After claiming the $30,000 contribution as a tax deduction, taxable income is reduced to $170,000.

- At a marginal tax rate of 47% (including Medicare levy), the tax saved: $30,000 x 47% = $14 100.

- Net tax saving after considering the 15% tax in the super fund: $14,100 – $4,500 = $9,600.

3.Additional Division 293 Tax:

- Kerry’s adjusted income = $170,000 + $30,000 = $200,000 (below the $250,000 threshold).

- No additional Division 293 tax is payable in this scenario.

Result:

Kerry reduces her taxable income to $170,000, saving $9,600 in tax.

Her super fund receives $25,500 after tax.